From the Yards to the Flag, the Student Army Training Corps

The Skiff, January 4, 1918

The Great War was an armed conflict that had a great impact on the development of military forces in great numbers. While the U.S. government mobilized troops quickly, it did not have much time to concentrate on the quality of training. An average American frontline solider had only 6 months of training.[1] In response, the military and government created new programs to develop young men mentally, militarily, and physically, such as the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) that came to universities such as TCU.

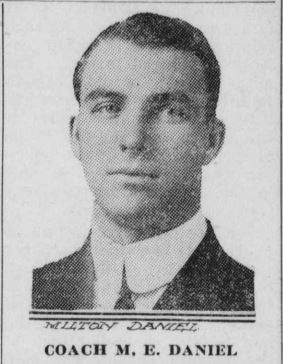

The story of the TCU SATC began in 1917. Football Head Coach M.E. Daniel listened to the requests of some of his students who had suggested that the university provide military-style training. He asked his students how many would take advantage of this training and the first numbers were between 150 and 200.[2] When Coach Daniel began military drills in December 1917, 125 men enrolled in TCU’s Military Class. By October of the following year, 320 were participating in the official SATC program.[3]

The Skiff, October 4, 1918

The SATC was a department of the United States Army, intended to train units of men in civilian higher educational institutions. These institutions were approved by the government to complete the following purposes: to qualify college students for effective services in the armed forces through systematic and standard methods of training. Students who completed their education would then be qualified to provide a reservoir from which candidates for Officers Training Camp may be drawn. This reservoir would then forestall an interruption in the nation’s supply of educated young men through premature enlistment and prepare the next generation of men mentally, morally, and physically through rigorous military discipline.[4]

The U.S. Army had to be clear about the military status of the young men enrolled in the program. Enlisting in the program exempted young men from being immediately drafted. SATC members were considered members of the Army. The government did not immediately call members of the SATC to the colors, until their number would have been reached under the Selective Service Regulations, or until he had finished the program, or any urgent military reason necessitated their services.[5]

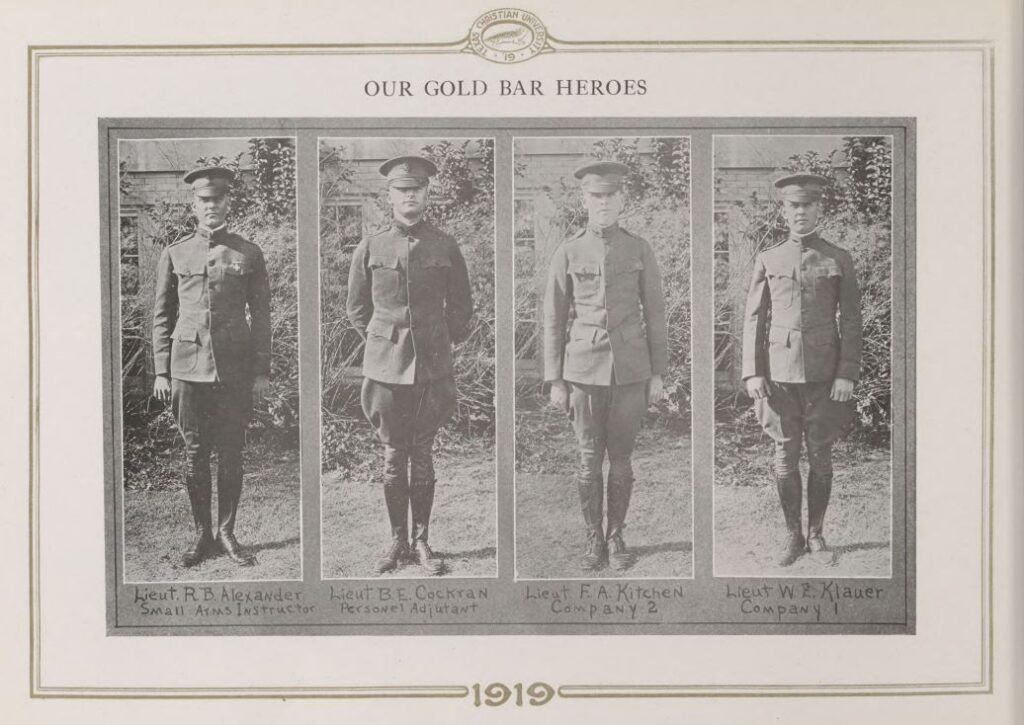

The structure of SATC was very well defined. By 1918, there were four officers in charge of the development of more than 320 students enrolled in the military training courses offered at TCU. The officers taught the courses and the physical training required to complete the U.S. government program.[6] The program was divided into forty-two hours of classroom work and supervised study each week, plus thirteen hours of actual military program. Ten hours of this program were spent in drill and three hours studying military science. Every student was required to take four courses, including the War Aims course to complete the program that started each day at 6 AM.[7]

SATC program numbers were increasing, due to enrollees’ satisfaction and greater interest among other students. However, the end of the war stopped the development of the SATC, and the program ended not only at TCU but also at five hundred other colleges by December 1918. The SATC program was short, but it was also successful in leaving a legacy of military development. This program planted a seed for later programs, such as the V-12 program of World War II, and today’s ROTC. TCU celebrated the end of the SATC and the return of the boys to college life in one of the biggest banquets this school had ever hosted.[8]

[1] “Getting American Soldiers Trained in the Realities of Trench Warfare,” American Battle Monuments Commission, November 2017, https://www.abmc.gov/news-events/news/getting-american-soldiers-trained-realities-trench-warfare.

[2] “T.C.U to Have Military Training,” The Skiff, December 7, 1917, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[3] “One Hundred and Twenty-Five Men Enter T.C.U. Military Class,” The Skiff, December 13, 1917; “320 Students Respond to Colors,” The Skiff, October 4, 1918, both in Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[4] “Military System Instituted at T.C.U.,” The Skiff, September 13, 1918, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[5] “Military System Instituted at T.C.U.”

[6] “320 Students Respond to Colors.”

[7] “Military System Instituted at T.C.U.”

[8] “Old Order Makes Way For The New Banquet To Celebrate Dissolution Of S.A.T.C.” The Skiff, December 28, 1918. Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

For Further Reading

“Getting American Soldiers Trained in the Realities of Trench Warfare,” American Battle Monuments Commission

This reading is very important for understanding the context of solider training for the frontlines during World War I. It describes the time spent on training and what happened to the first American soldiers on the Western Front.

Neiberg, Michael S. Making Citizen-Soldiers: ROTC and the Ideology of American Military Service (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Neiberg provides the context for universities and societal changes of the era. He does not discuss TCU specifically, does write about Texas and other institutions where student military training was established.

Ginchereau, Eugene. “The American Ambulance in Paris, 1914-1917 Part II: The University Surgical Service.” Military Medicine 181, no. 1 (January 2016): 3-4.

Article gives a sense of the patriotic duty that was trying to be implemented in the S.A.T.C. It changes the perspective that many had about American mentality towards war and what others were trying to accomplish in a country that was severely affected by the war and their purpose of helping others.