Horned Frog Reaction to the Day of Infamy

The Horned Frog reaction to the infamous day of December 7, 1941 was no different from the same reaction average Americans had across the country. Outrage, excitement, anxiety, and a new sense of purpose was felt throughout campus. Many TCU students dropped out to enlist, while others heeded Dean Sadler’s advice to finish their education before answering America’s call.[1] As the days and weeks went on, the student newspaper tried its best to keep track of the former Frogs who had gone off to serve.

TCU Skiff, December 19, 1941.

Only one Horned Frog was at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, Buster Nicks, a marine serving aboard the USS West Virginia.[2] The first to leave and enlist was Harvey Glasgow who signed up for the Navy on December 9, his 19th birthday.[3] Many more students would see combat throughout the war, motivated by the headlines and tales of destruction that came over the wireless.

Other students had close relatives that were overseas or in the service when war came. Jane Jones had a brother, Gerald, who was in Java on December 7 and narrowly avoided the ensuing Japanese invasion.[4] For many the toughest was the uncertainty of those early days of the war. Not knowing whether their loved ones or even themselves would have to go overseas and fight the war that had ripped away their college experience.

Reeling from the sudden attack on Hawaii, TCU students just like the rest of America were gripped with anticipation of a Japanese invasion. Students on campus were chosen to serve as air raid wardens during the first campus blackout. The students involved in the drill’s reaction was mostly disappointment at the lack of Japanese paratroopers on campus to wrangle with.[5] In those early days students displayed a lack of understanding to the reality of the war to come.

Another major development during the war was the uptick in student marriages.[6] This was not uncommon throughout the United States during the war. In 1942 alone over 1.8 million weddings took place across America, up 83% from 10 years before.[7] Many young men went off to fight and they married their sweethearts and girlfriends so they would have something to come home to when they got back.

TCU Skiff, January 16, 1942.

TCU Skiff, February 6, 1942.

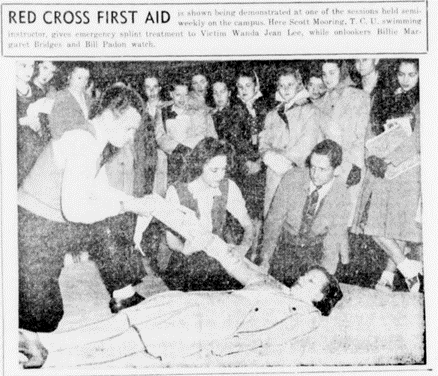

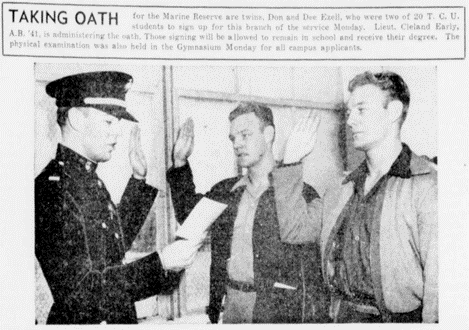

Among those who went off to serve there was a noticeable trend towards airmen, both in the Navy and the Air Corps. Prior to the start of the war TCU offered membership into the Civilian Pilot Training Program, and this allowed many Frogs to go into the service not only as officers but also as aviators. This was not the rule however, and several students joined the service as junior enlisted men, despite their college experience. While news of further attacks on Guam, Wake Island Manila and other locations scattered headlines of local newspapers like the Star-Telegram, TCU students went about their lives on campus. The juxtaposition of stories about enlistment programs and Red Cross classes sharing the page with gossip columns on relationships through the student body speaks volumes to how untouched many on campus were, even in Americans’ darkest hour. The basketball team continued to play, and student body elections were still held. The ability for those on the home front to attend school, live their lives in freedom, and pursue innocent dreams and productive futures It was this lifestyle that our nation was truly fighting for.

The Horned Frogs of the greatest generation were ordinary American kids. Like so many others they answered their nation’s call-in light of the “sudden and dastardly attack” against the United States.[8] Those who did not serve stayed home and developed skills to lead our nation in the aftermath of the conflict and gave our young men something to return home to.

[1] “Sadler Advises Students to Stay in School,” The Skiff, December 12, 1941, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[2] “World War II Finds 253 Frogs on TCU Service Honor Roll,” The Skiff, May 22, 1942, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[3] “Students Faculty Philosophize As Japanese Treachery Forces US Into World War,” The Skiff, December 12, 1941, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[4] “Students Faculty Philosophize As Japanese Treachery Forces US Into World War,” The Skiff, December 12, 1941, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[5] “All’s Quiet on the TCU Front,” The Skiff, January 23,1942, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[6] “Should Marriage Come Before or After Second World War,” The Skiff, February 26, 1942, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[7] “Lining up for Wartime Weddings,” New York Times, February 2, 2017.

[8] Roosevelt, Franklin D. “Address to Congress Requesting a Declaration of War with Japan,” December 8, 1941, The American Presidency Project. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-congress-requesting-declaration-war-with-japan.

For Further Reading

Walker, Fred L. From Texas to Rome (Dallas: Taylor Publishing Company, 1969).

This book is an account of the 36th Infantry Division and its actions in North Africa and Italy during the early phases of the war in Europe. It is written by Division commander Fred L. Walker and recounts the experiences of the “Texan Army” during its baptism of fire and beyond.

Prange, Gordon W. At Dawn We Slept (New York: Penguin, 1991).

One of the most extensive accounts of the attack on Pearl Harbor, this book covers the failures of the American military intelligence to spot the warning signs leading up to the surprise attack on the Pacific Fleet, the raid itself from various viewpoints, and its aftermath. If one is wanting to learn more about December 7th, this work helps to understand just how and why the United States Navy allowed itself to suffer their worst defeat.