Forgotten Female Soldiers of WWII

Despite the history of women’s military service, the American public has not seen them as integral to the success of the military due to the military’s masculine culture and the social construction of gender roles.[1] Women who served in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during and after World War II faced societal pressure to conform to the expectations of womanhood and had a difficult transition back into society, including female veterans who attended TCU on the G.I. Bill after the war.

During the 1940s, tradition encouraged women to look and act in a way that maintained their dependence on men and encouraged proper womanhood, which meant maintaining the home front and supporting the boys so that men would embrace their role of protectors.[2] Americans defined the female role of appearance and agreeability during the war. Many people held women with these qualities in high regard. Even in wartime production jobs, women needed to maintain their femininity to avoid becoming “man-ish,” which threatened their ability to get married. When many Americans expected women to enjoy makeup and patriotically support the war from home, it was not mainstream or easy to be a woman in the Army.

WACs served in an official military capacity, and despite often serving in traditional feminine clerical, administrative, or communications work, they challenged the societal expectation of womanhood and often clashed with the public perception of women’s roles. Many Americans feared established gender, sexuality, and racial roles would change if women were permitted to serve and act as soldiers. To many, women and soldiers were mutually exclusive parties with no room for overlap. Military men attacked the WAC in a slander campaign to undermine its credibility and attacked women’s character.[3] However, the WAC itself illustrated the change that many women desired. Women in the WAC did not want to be restrained by their expected social roles and desired lasting change from their service in the Army. WACs had more social freedoms than civilians because they challenged gender roles. Although the Army monitored WACs’ activities, they could interact with new people worldwide and stand up for themselves through military service. The WAC forced Americans to reconsider the gender roles and expectations that had been in place before World War II. However, despite the significance of the WAC as an institution that challenged social hierarchies, when women left those positions, they struggled to readjust to a society that valued more simplistic and dutiful roles for women.

Mary Edna Welke, Isabel Lenore McAllister, and Myrtle McLeroy Maxwell, and emphasizes the difficulty for them to readjust to society.

After the war, WACs utilized the G.I. Bill to attend schools like TCU, but their wartime experiences and the lack of support for female veterans did little to aid in their readjustment to society. The G.I. Bill significantly boosted educational opportunities for all veterans after the war, but women often needed a man to fully utilize the G.I. Bill’s benefits. Although female veterans were more likely to attend college than other women because of the G.I. Bill benefits, they were statistically less likely to finish college and graduate.[4]

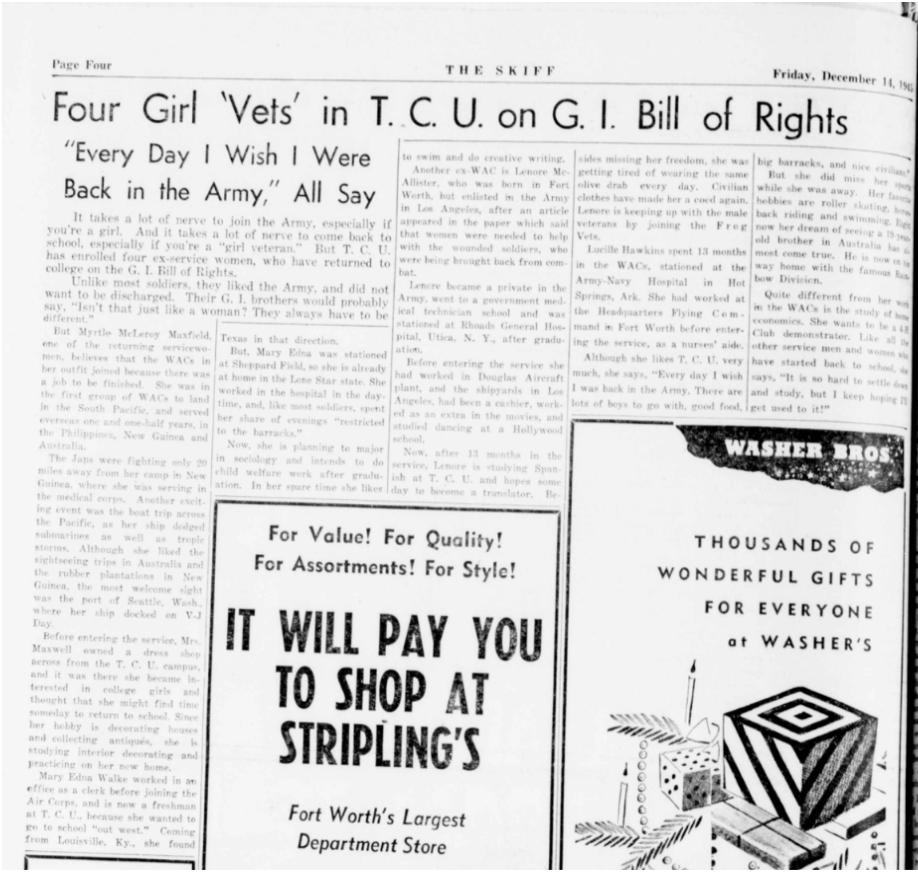

This statistic is accurate for the female veterans who came to TCU in 1945, including Lucille Hawkins, Mary Edna Welke, Isabel Lenore McAllister, and Myrtle McLeroy Maxwell.[5] These women were stationed all around the globe during the war, from Texas to New York, Arkansas, and the South Pacific. By 1945, they all arrived at TCU on the G.I. Bill. These women were at TCU for at least two years, and Hawkins was a student for three, but none of these women graduated from TCU, as indicated by the lack of commencement records.[6] Research in TCU Special Collections provides little on their military or college experience. Still, one thing is clear: they struggled to readjust to civilian life as women who had challenged social norms, and TCU did not have organizations to support female veterans specifically. Mary Edna Welke joined the TCU American Legion veterans organization, but she was the only woman involved in 1946, which shocked TCU students who had more traditional views of gender.[7] These women wished to be back in the army and struggled to settle into college. One cannot help but wonder why women who started with large aspirations in a variety of majors never adjusted to college life.

These women were bold in their desire to serve in the military and challenge the notion that women could not be soldiers. They lacked institutional support coming home, and the missing documentation for their military and college experiences emphasizes this. Despite their significant efforts in the war, their stories have been lost in American military history.

[1] Michael D. Gambone, The New Praetorians, American Veterans, Society, and Service from Vietnam to the Forever War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), 133-145.

[2] Melissa A. McEuen, Making War, Making Women: Feminity and Duty on the American Home Front, 1941-1945 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

[3] Leisa D. Meyer, Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II (New York: Colombia University Press, 1996).

[4] Conor Lennon, “G.I. Jane Goes to College? Female Educational Attainment, Earnings, and the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944,” The Journal of Economic History, 81, no. 4(December 2021): 1223-1253.

[5] “Four Girl ‘Vets’ in T.C.U. on G.I. Bill of Rights,” The Skiff, December 14, 1945, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[6] TCU 1947 Catalog and TCU 1948 Catalog, both in Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

[7] “Welke Walks Alone- Former WAC on Legion Roll is Feminine Touch to Vets,” The Skiff, May 24, 1946, Special Collections, Mary Couts Burnett Library, Texas Christian University.

For Further Reading

Leisa D. Meyer, Creating GI Jane: Sexuality and Power in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II (New York: Colombia University Press, 1996).

Leisa Meyer explores themes of sexuality and power in her book Creating GI Jane. She argues that the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) challenged and upheld social hierarchies of sexuality, gender, and race by combining femininity with military service. This book provides a cultural context of the WAC and outlines a brief historical interpretation of the public response to the WAC.

Melissa A. McEuen, Making War, Making Women: Feminity and Duty on the American Home Front, 1941-1945 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011).

Melissa McEuen explores the social expectations of femininity and gender roles during World War II. She focuses mainly on physical appearance to convey her argument that gender roles were strict during this era but greatly influenced post-war culture. This book provides the context for the social expectations of womanhood and the general societal trends during the war.

Michael D. Gambone, The New Praetorians, American Veterans, Society, and Service from Vietnam to the Forever War (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2021).

Michael Gambone focuses on the lasting patterns and trends of female military service, arguing that history is full of female veterans not getting full recognition of service. A chapter about women discusses issues that women in the military faced over time and provides context for the historical idea that the military has overlooked them in United States military history.